Understanding the spectrum analyzer principle is fundamental for RF engineers, system designers, and test & measurement professionals. A spectrum analyzer converts time-domain signals into the frequency domain, allowing engineers to evaluate signal bandwidth, spurious emissions, phase noise, harmonics, and interference.

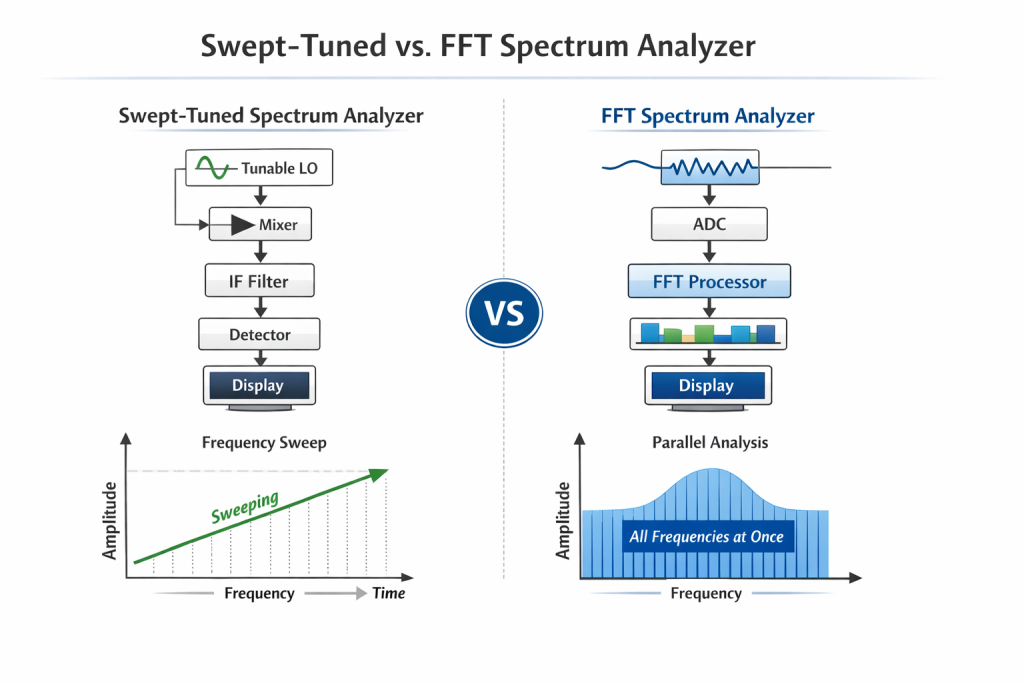

Modern spectrum analyzers are primarily built on two distinct architectures: swept-tuned spectrum analyzers and Fast Fourier Transform (FFT)–based spectrum analyzers. While both aim to display signal power versus frequency, their internal mechanisms, performance trade-offs, and application suitability differ significantly.

This article analyzes these two approaches from an R&D engineer’s perspective, incorporating mathematical foundations, system-level considerations, and references to authoritative international publications.

Fundamentals of the Spectrum Analyzer Principle

At its core, the spectrum analyzer principle is based on transforming a signal from the time domain into the frequency domain. The continuous Fourier Transform is defined as:

X(f)=∫−∞∞x(t)e−j2πftdt

This equation expresses how a time-domain signal (x(t)) is decomposed into its constituent frequency components. Practical spectrum analyzers implement this transformation either through frequency sweeping using analog hardware or through digital sampling followed by FFT computation.

The choice of implementation directly affects frequency resolution, dynamic range, measurement speed, and the ability to capture transient signals.

Swept-Tuned Spectrum Analyzer Principle

Superheterodyne Architecture

The swept-tuned spectrum analyzer is the traditional and historically dominant design. It is based on a superheterodyne receiver architecture, widely used in RF communication systems. The analyzer sequentially scans through a defined frequency range using a tunable local oscillator (LO).

The signal processing chain typically consists of:

- Input attenuation and preselection filtering

- Frequency down-conversion via a mixer

- Fixed intermediate frequency (IF) filtering

- Envelope detection and logarithmic amplification

- Synchronized frequency sweep and display

As the LO sweeps across frequencies, only signals within the IF filter bandwidth are detected at each moment, forming a complete spectrum over time.

This swept-tuned spectrum analyzer principle is mathematically analogous to a narrowband filter sliding across the frequency axis, measuring signal power point by point [1].

Strengths and Limitations

Swept-tuned spectrum analyzers offer:

- Wide frequency coverage (from kHz to millimeter-wave)

- High dynamic range and excellent sensitivity

- Mature hardware architecture with stable calibration

However, they exhibit inherent limitations:

- Inability to capture short-duration or transient signals

- Potential to miss intermittent interference events

- Sweep time increases with resolution bandwidth and span

These limitations become critical in modern systems involving frequency hopping, burst transmissions, or dense spectral environments [2].

FFT Spectrum Analyzer Principle

Digital Sampling and FFT Processing

The FFT spectrum analyzer principle relies on high-speed analog-to-digital conversion (ADC) followed by digital signal processing. The input signal is sampled at a rate satisfying the Nyquist criterion:

fs≥2B

where (fs) is the sampling frequency and (B) is the signal bandwidth.

A block of (N) time-domain samples is then processed using the Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT), efficiently computed via the FFT algorithm:

X(k)=n=0∑N−1x(n)e−j2πkn/N

This approach computes the entire frequency spectrum simultaneously rather than sequentially [3].

Windowing and Spectral Leakage

In real-world FFT spectrum analyzers, window functions (e.g., Hanning, Blackman-Harris) are applied to mitigate spectral leakage caused by finite time records. Window selection directly influences amplitude accuracy and frequency resolution—an important consideration for precision measurements.

Swept-Tuned vs. FFT Spectrum Analyzer: Engineering Comparison

Performance Trade-Offs

| Parametro | Swept-Tuned Spectrum Analyzer | FFT Spectrum Analyzer |

| Frequency acquisition | Sequential scanning | Parallel processing |

| Transient signal capture | Limited | Excellent |

| Gamma dinamica | Molto alto | ADC-limited |

| Measurement speed | Sweep-dependent | Near-instantaneous |

| Complexity | Analog RF-intensive | Digital DSP-intensive |

From a spectrum analyzer principle standpoint, swept-tuned designs excel in stable, continuous signal analysis, while FFT-based designs dominate applications requiring real-time spectrum awareness [4].

Real-Time Spectrum Analysis and Hybrid Architectures

Modern real-time spectrum analyzers integrate overlapping FFTs, deep memory buffers, and FPGA-based processing to eliminate blind time. These instruments guarantee a probability of intercept (POI) for signals above a specified duration and amplitude.

To address frequency coverage limitations, many high-end instruments employ hybrid architectures, combining swept-tuned front ends with FFT-based digital IF processing. This design merges wide frequency range with real-time detection capability, reflecting current industry trends [5].

Engineering Application Considerations

From an R&D perspective, the selection of a spectrum analyzer architecture depends on application requirements:

- EMI/EMC compliance testing often favors swept-tuned analyzers for their dynamic range.

- Wireless protocol development and interference hunting benefit from FFT and real-time spectrum analyzer principles.

- Advanced modulation analysis typically requires FFT-based digital processing.

Understanding the underlying spectrum analyzer principle allows engineers to interpret measurements correctly and avoid misdiagnosis caused by instrument limitations.

Conclusione

The spectrum analyzer principle is implemented through two fundamentally different methodologies: swept-tuned frequency scanning and FFT-based digital spectrum analysis. Swept-tuned analyzers rely on superheterodyne architectures and sequential measurement, while FFT analyzers use high-speed sampling and parallel frequency computation.

Each approach presents unique advantages and constraints. As RF systems grow more complex and dynamic, FFT-based and hybrid spectrum analyzers are increasingly essential. However, swept-tuned analyzers remain indispensable for wideband, high-dynamic-range measurements.

A solid grasp of these principles is critical for RF engineers engaged in system design, debugging, and validation.